The Care Cap Con?

It’s not a particularly fun topic is it - having to pay for care?

It is however a real concern for many and the truth is, it’s a complete minefield to navigate.

It’s not getting any simpler, anytime soon.

Social care is an overarching term that generally describes all forms of personal care and other practical assistance for children, young people and adults who need extra support.

Unlike the NHS, social care has never been free at the point of use.

If you do require social care there are a needs test and a means test which are used to determine if someone’s care needs are eligible for the State to contribute towards.

It is only if someone’s needs are high enough and their wealth low enough do they qualify for financial support from the state.

The potential cost of care is, painful. The average weekly cost of living in a residential care home is £704, while the average nursing home cost is £888 per week across the UK. So think potentially around £36k-£46k per year. There are large regional differences to be aware of, so if you live in the South, the costs may be considerably higher.

A simplified version of what you need to know - ‘the means test’

*I must make clear, that the purpose of this blog is not for a comprehensive review of all the means tests and rules (as that would take a very long time.) So I am heavily simplifying some areas and rules, please do seek advice specific to you if you find yourself or a family member needing support in this area.

If you are not eligible for NHS-funded care and you are seen as needing care. There is then an assessment made based on your income and capital on whether you will receive Local Authority support.

A large misunderstanding is that care is potentially paid by local authorities purely based upon some prescribed tests based on how much ‘capital’ you have. This is not wholly true, if you have £100,000 in income and your care costs £50,000 per year, you are paying for your care yourself. There are no additional tests made.

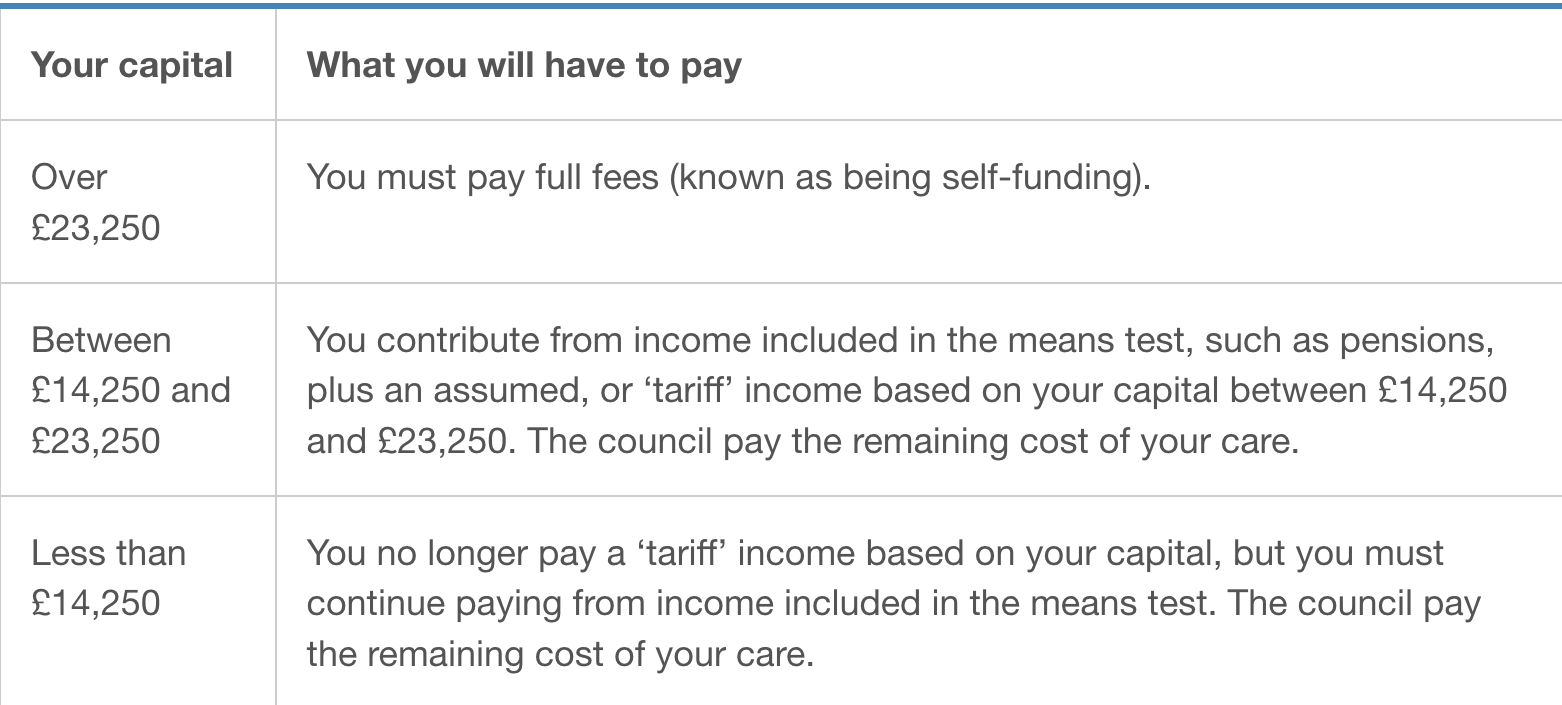

If you do not have income to meet the costs of your care. There is a test based on the capital you have. The current thresholds are:

(Source -AgeUK)

This will however change. In line with the new reforms. From October 2023 this will change to:

Although certain types of income, such as money from certain disability benefits, are ignored in the means test. This is the same for certain types of capital. All other income and capital can be taken into account.

What about the family home?

The family home is often an understandably emotive aspect of being considered ‘capital.’ It strikes a nerve with many people. After all, having spent decades paying interest on your mortgage the concept of then having to sell the home to pay for care can be a real concern.

If you need short-term or temporary care in a care home, your home won't be in the means test.

If your property is going to be included in the permanent care home means test, the council must ignore it for the first 12 weeks of your care.

If your care home is permanent, it won't be counted if it's still occupied by:

your partner or former partner, unless they are estranged from you

your estranged or divorced partner IF they are also a lone parent

a relative who is aged 60 or over

a relative who is disabled

a child of yours aged under 18

This often leads people to drastic measures to reduce the value of their assets. This is a thorny and difficult issue as there are many rules over ‘deliberate deprivation’ and if you fall foul of these. The local authority can decide to treat you as if you still possess the asset for the purpose of the financial assessment.

The problem and concern for many are that our social care system is extremely difficult to plan for financially. With a distribution of outcomes being highly skewed.

Some pay nothing for their care as they never need it (who would have thought the old ‘sudden heart attack’ could be framed positively?)

For some, costs can escalate in the hundreds of thousands.

It is the most bizarre version of - do you feel lucky?

The ‘cross subsidy’ problem

The market for social care is also deeply dysfunctional. With a ‘self-funder levy’ occurring in most care homes. Local authorities have the ability to bulk-buy beds so have high purchasing power.

A consequence of this is there is often a huge cross-subsidy between private funders and local authorities. Effectively, to make the numbers work care providers have had to put a premium on self-funders, those who privately pay for their own care.

To put it simply - you could be sitting in the same bed, receiving the same quality of care in a home and the person in the same quality room next door who is ‘local authority paid’ could be paying 25% less than you would pay as a self-funder.

As you can see in the purple bar compared to the yellow bar, there is a significant difference in the weekly costs.

This was one of the issues the Government was trying to address with the reforms.

But my care costs are capped at £86,000 right?

That would have been a very fair thing to have thought based on the headlines and of course, the government messaging.

There are however some costs which are not included in counting towards the cap. Once you look into this, you’ll notice how massive the T&Cs are. Costs that don’t count are:

Cost of meeting eligible needs before October 2023

Costs that the Local Authority do not ‘deem’ as eligible. - This could catch quite a few people out as this could mean someone could potentially be living in a care home currently but the severity of their needs is not considered severe enough to typically need support. In essence, a family could deem the individual in need of care home support but the Local Authority may not and in that instance, it would not go towards the cap.

Daily living costs - this includes daily costs of living, food, accommodation etc.

Any amount being paid in excess of what the Local Authority would pay to meet their eligible needs - want a better room that you’ve been given? Not going to count towards the cap.

Any top-up payments - family helping out towards the care? Not going towards the cap.

Any financial contribution from the Local Authority - yea, fair enough. If the Local authorities are already paying then it’s not going to count towards the cap.

As you can see, the list of things that are not included is much longer than you might initially have thought. This is because what is defined as ‘personal care’ is much broader than we’d expect. The below shows a typical illustration of what would be reasonably expected to pay, with the orange amount being the contribution towards the cap.

In this illustration, it would take 217 weeks to get to the cap, which they would have been paying £1,100 per week.

They would have paid £238,700 to achieve the £86,000 cap.

The average time that most spend in a care home is around 2 years, however, averages clearly have no impact on an individual’s circumstances. If someone enters a care home in reasonable health they could live there for much longer.

Research from Kings Fund noted that due to this, some people could still see more than 70 per cent of their savings and wealth go towards care costs.

So is it easier to plan now the ‘cap’ is in place?

As you may have already inferred, the answer is - not really.

The reality of the care cap in its current form is that individuals could still be hundreds of thousands out of pocket in the process of paying for their own care. The rules remain fiendishly complex and it creates a large position of uncertainty.

We can’t lose sight of the fact there are huge potential benefits of a genuine, robust cap on care fees. Life insurance (or in fact any insurance) is an example of the business of profitably managing skewed outcomes. When you take our life insurance at 40 years old. The insurer is able to offer reasonable premiums on the basis that while it fully expects that some pass away before their time. As most will not, they can then price the premiums relatively affordably.

If we can create a true, fit-for-purpose cap on the care it could open options for financing pre-funding. This was the promise sold with the Health and Social Care Levy.

I can’t make any claims on policy suggestions but surely some interaction with tax relief and pension legislation could surely create some scope for integration. This must surely be a risk we can plan and mitigate.

As far as funding, through this current levy, it is projected that only £5.4bn of the £39bn projected to be raised is going towards social care will go towards social care. With the rest going to post-COVID recovery, many feel this is not enough.

Some independent researchers have stated that true, social care reform would in fact cost between £40bn, with some independent groups stating figures up to £80bn.

While our new Prime Minister voted in favour of the Health and Social Care Levy. We remain in politically uncertain times. There is talk of scrapping the NI levy with no alternative plan in place for additional social care funding. There are around 1.5 million people working in social care currently and huge amounts of citizens are facing the reality of care.

It is difficult to be satisfied with the current proposals.

Perhaps not a con, but certainly not clear.

DISCLAIMER - This blog piece is a brief overview of what is a very complex issue, with legislative differences across parts of the UK. This blog is for informational & educational purposes only., It SHOULD NOT be relied upon in isolation to make any financial decisions. Please seek advice specific to you before making any financial decisions. The views stated are individual and may not represent those of my employer. The information provided in this presentation has been compiled from sources believed to be reliable and current, but accuracy should be placed in the context of the underlying assumption

Sources used in this article - MyCareConsultant, AGEUK,